Power Play

Celebrities bemoan the drawbacks of being rich and famous but being poor and famous is far worse. Derek Mackintosh had, for a few years, been the former and was now very much the latter. That was why he was standing outside Costcutter, waving his arm at an approaching W7 bus to Finsbury Park, rather than hailing a taxi.

As the bus pulled in, Derek steeled himself to face the driver. First there would be the quizzical look; then the moment of recognition and the inevitable question. Yes, he was that bloke from the telly. He’d remind the driver of his name, as if to verify that his really was the face on the bus pass, and shuffle past, in search of a seat, conscious of the unabashed stares of the other passengers.

There might be a request for an autograph – usually from someone of his own age – or, more often, from someone half his age, a selfie, that would quickly find its way on to some social media site.

“OMG. Look who I met on the bus today. The King of America himself!!!”

And, at some point, someone would offer some variation on: I’d never have expected to see someone famous like you using the bus. He'd never expected it either. But then, he hadn’t expected a hit show to be cancelled while seemingly at its peak. Or the drinking, the affairs and the divorce that had come with its success.

He got off near the tube station, making his way past a collection of wooden pallets and a discarded washing machine. Food packaging was blowing along the broken pavement, moving faster than the four lanes of fuming traffic.

He paused outside an estate agent, next to a betting shop, and was shocked at the prices being asked. For a moment, he had entertained the idea that his half of the money from selling the house in Muswell Hill would be enough to pick up something around here. A quick look at the flats on offer soon killed that thought.

The church hall was freezing. He’d opted for an early slot, wanting to avoid running into any of the other hopefuls, but that meant that the heating had only just been switched on. His audience, perched tensely on plastic chairs, were still in their coats.

The director – about 30 and sporting a goatee – was wearing an Arsenal bobble hat. A local, Derek thought. That’s why we’re in this dump.

“We’re very excited that you’re interested in the part,” declared the producer.

“Neither of the leads have headlined the West End before, so a well-known name on the bill would be a big plus.”

And then, from the director, the inevitable question.

“So, what have you been doing since King of America?”

Derek had his answer ready. It was the one he always gave.

“I decided to take a bit of a break. Nearly a hundred episodes in three years was pretty gruelling - especially with all the publicity and everything. I had to call a halt.

“I’m writing my autobiography. I’m not using a ghost writer, so every couple of weeks I get a nagging phone call from my publisher. It’ll be finished before rehearsal starts, though.”

The director nodded knowingly, acquiescing in the deceit.

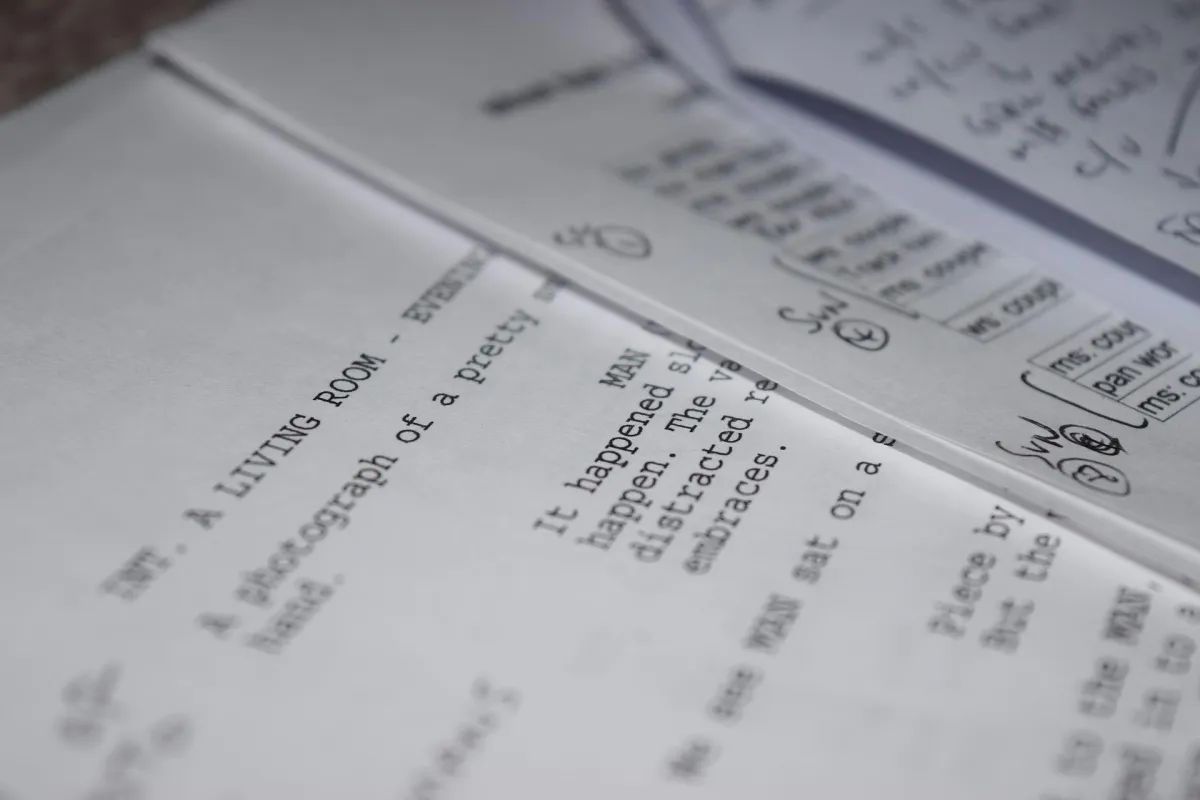

“OK, well let’s go. Big father-daughter confessional scene, so lots of emotion. Gwendoline here will read with you.”

The director’s assistant, a short, plump woman in a pink anorak stepped forward. Not quite the morally-ambivalent temptress implied in the script, thought Derek.

He closed his eyes to blot out his surroundings and place himself in a Tennessee trailer park, in the skin of the errant father begging his daughter’s forgiveness for twenty years of misery.

There was a shopping list of setbacks - a broken marriage, unsustainable expectations, lost jobs, drink, drugs, rejections and put-downs. It was a lengthy soliloquy; the resumé of a broken man.

On Gwendoline’s cue, he began to speak. He slipped into the accent like a warm sock, his voice deepening and speech slowing, at first to a mumble, as his character stumbled through his litany of inadequacies, then getting louder and clearer as the anger built, before climaxing in a howl of anguish.

“And every day you pretend that everything’s fine, but all the time you’re being crushed by failure after failure after failure. Then one morning you realise that the only thing you will ever get right again in your life is to die.”

He paused, waiting for Gwendoline to deliver her line. She was staring at him, mouth agape and tears welling up. He glanced across to the others. The producer was completely motionless, as if petrified. The director, equally still, avoided his eye, looking down at his notes.

At that moment, Derek knew that he held them in his command, an absolute monarch in his imaginary court.

Another man – presumably the next candidate – had slipped into the room and stood silently at the back. I’ll own you too, thought Derek.

He turned back to Gwendoline, who shakily delivered his cue for the scene’s denouement. He took his voice down to a whisper, seeing from the corner of his eye the director and producer leaning in to hear him. Forcing out tears, sobbing, he fell to his knees, finally grabbing at the hapless assistant, burying his face against her thighs with a wailing plea for forgiveness.

There was a silence, broken only by Derek’s heaving breaths as he clung to Gwendoline’s legs. The man at the back began to clap. The producer joined in, followed by Gwendoline herself.

Derek hauled himself to his feet and, exhilarated, gave an exaggerated bow towards the director. Their eyes locked for a moment and Derek felt the power slip away from him with the sinking, familiar, recognition that, at court, if you are not the king then you are a potential usurper.

The director smiled thinly.

“Thank you, Derek. We’ll let you know.”

First published in Lucent Dreaming issue 9 - digital and print copies are available from Lucent Dreaming's online shop.

Image by Oli Lynch on Pixabay