Losing My Religion

Some thoughts on riding

London-Edinburgh-London 2017

There were so many times when I was ready to give up.

– Being forced of the road by an impatient driver near Castle Howard;

– Having my hands and wrists battered by the third world road surfaces between Gretna Green and Edinburgh;

– Wrapped in a blanket at Barnard Castle, trying to get dry and warm after an horrendous crossing of Yad Moss southbound;

– Grinding across the Fens in low gear in the face of a relentless headwind;

– Forcing myself to get some sleep at St Ives after hallucinating for the previous 20km and working out that I was not going to get back to London within the time limit.

All were moments – and there were others – when I allowed myself to consider abandoning my attempt to ride from London to Edinburgh and back again in 117 hours.

Well, I didn’t. And while my reasons for deciding to continue at each opportunity to quit might not have been particularly admirable, I think that in continuing I dug deeper into whatever inner resources I have than I have ever done on a long-distance bike ride before. And I liked what I found there but I’m worried about how it has left me feeling.

But I’m getting ahead of myself…

Begin the begin

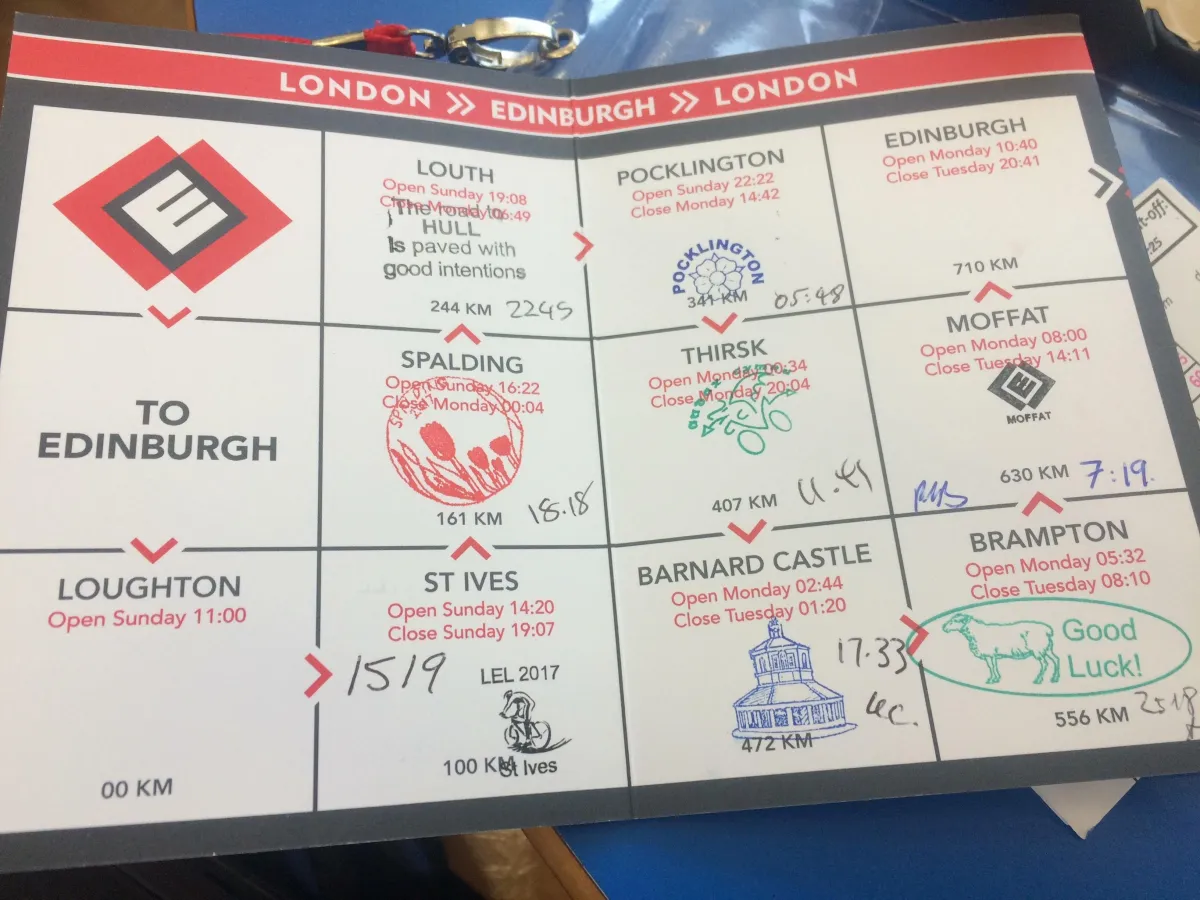

Rewind to 9am, Sunday July 30th. I’m cycling towards Loughton, on the north-eastern edge of London for the 8th staging of the London-Edinburgh-London (LEL) randonee. (For the uninitiated, a randonee is a cycling event in which riders have to cover a set distance within strict time limits and without any support on the road. It’s not a race, so there is no winner; all that matters is finishing.) I’m joining 1,499 others* from 55 countries. Ahead are 1,441 kilometres with 11,128 metres of climbing. My start time is 11.00 am and I have to be back by 8.05 am on Friday.

I think I know what I’m in for. The 6th LEL in 2009 was widely agreed to have been the toughest so far, with appalling weather in the Scottish Borders bringing fierce winds and flooded roads, but I finished comfortably.

The route has changed a little since then but still follows the basic thread of heading up through eastern England to Scotch Corner, crossing the Pennines towards Carlisle and then over the more rolling hills of the Scottish Borders to Edinburgh. And reverse.

I’ve traced it out on the map, even though I’m using a Garmin GPS unit as my primary means of navigation, and provisionally planned my eating and resting time at the various checkpoints (known as “controls”) so that I should be back in Loughton on Friday morning with a least a couple of hours to spare.

I’ve even booked a couple of hotels, in Edinburgh and South Yorkshire, so I can get a decent shower and a few hours in a proper bed – something I’ve never tried on a randonee before.

So I’ve planned for success. On the other hand, I’m apprehensive about my fitness levels. I’ve not done as much training as I would like to have and on a couple of 400km and 600km rides in recent months I’ve struggled to finish within the time limits. I’ve also abandoned two 300km rides after just 200km or so simply because I wasn’t enjoying them. But having worked as a volunteer, running a kitchen, on the 2013 edition, I had a guaranteed place in this year’s event – and it would have been a shame to waste it….

…and so, on the stroke of 11.00, in my group of about 50, I’m off.

And at about 11.02 I’m at the side of the road watching the rest of them disappear up ahead while I try to figure out why my Garmin is telling me that I am already off course.

The problem’s quickly sorted and I soon catch up with the back end of the group. We’ve been started at 15 minute intervals since 5.00 am; the final group is due to start at 4.00 pm.

Each rider has a frame badge with a letter and number combination that indicates his or her start time. The first riders were Group A, and so on. In the early part of the ride, it becomes second nature to check other riders’ numbers as you pass them or they pass you. Being in group S, I’m not ashamed to admit that I feel a little buzz of pleasure when I pass my first rider from group R, as well as a pang of envy when overtaken by a pace line sporting group T badges.

As for the group X rider who shoots past me barely 40km into the ride – well, I hope he got to stop and smell the flowers at some point.

As group S starts to spread out, I hook up with a couple of others – Tony, whom I know from when he used to live near me and who rode LEL in 2013 but had to pull out through injury, and Alison, a rider from Welwyn, who cheerfully tells me that she has never ridden more than 300km before. I admire her chutzpah; she seems to be a strong rider but I know from experience that being fast over short distances is not necessarily an advantage on long distance, multi-day rides.

Out in the country

We’ve got a bit of a tailwind and make good time to the first control, St Ives, at 100km. A half hour break for a quick snack and we’re off on the flat roads to Spalding. Another half hour break and more flat roads as we head towards Louth. Of the three of us, I’m the only one to have completed an ultra distance event (four, in fact) and, although I’m cracking the whip to get us through the controls quickly, I’m a little concerned that our pace on the road is too high for this stage of the ride. Basically, Alison and Tony are riding just a little bit faster than I want to. With the hills ahead once we cross the Humber, there’s no sense wasting energy just to get to a control a quarter hour earlier so, about 20km from Louth – as we approach the small climbs of the Lincolnshire Wolds – I ease off a little to chat with another rider and let them go ahead. I still reach the control earlier than I had anticipated.

There’s been some criticism of the Louth control; apparently it ran out of food as the later starters were arriving, but I experience no problems. Tony and Alison want to get some sleep - a mistake this early in the ride, I suggest - but I enjoy night riding and have a vague desire to cross the Humber Bridge at dawn so I leave at about 00.30. I’ve stayed longer than planned, mainly due to encountering riders that I’ve met on previous events and spending too much time chatting.

As it happens, despite some lumps between Louth and the Humber, it’s still dark when I cross the bridge and I reach the Pocklington control at a quarter to six. I’ve got bag drop here with some fresh clothes so I get to change as well as having a huge breakfast, but once again I stay too long. This is becoming a habit and I’m going to pay for it later.

About 25km from Pocklington, around Castle Howard and on towards Hovingham, is where the ride starts to get persistently lumpy and my pace drops – probably by too much. I waste too much time at the next control, Thirsk, and again at Barnard Castle, the control at 472km. I’m still on track to get to Edinburgh in 48 hours but I’ll need to be a bit quicker when I’m off the bike to compensate for the more challenging terrain.

From Barnard Castle the road climbs steadily, dips, and climbs again before plummeting down into Middleton in Teesdale. My memory of riding this in 2009 is that it was a bit of a slog, with far too much fast traffic, but today the traffic is light and I don’t really notice the climbs.

Next up is the centrepiece of the ride, the climb over Yad Moss. It’s one of the highest roads in England, at 596 metres, and boasts the country’s only ski resort. I was hoping to get over in daylight but I stop to take some photos of the Tees valley and so the sun is finally dropping over the horizon as I start the descent.

Just over the top, I come across a French rider at the side of the road with his bike upturned. His English is as sleep-deprived as my French but I soon work out that he has ripped his rear tyre and has no means of patching it so that it will shield an inflated inner tube from the road. It’s about 12km downhill to the next control, at Alston, and it’s starting to drizzle.

I’ve played my next decision over in my mind several times since the event and I still don’t know if I did the right thing or not. I’ve got a spare tyre in my saddlebag. It’s wider than his split one but would probably fit his wheel. Should I offer it? If I give it up, the chances of obtaining a replacement before I get to Edinburgh are slim – and I know that the roads ahead can be rough. I opt for self-preservation. I promise to go to the next control – which I had originally planned to miss as it wasn’t a mandatory stop – and alert the volunteers there to his plight. Knowing the lengths to which volunteers on LEL will go to help riders in difficulty, I am confident that, at the very least, someone will drive back up the hill to pick him up.

The school hosting the Alston control takes a bit of finding in the dark, but when I do get there my confidence isn’t misplaced. A volunteer heads off into the night either to help with a repair or bring rider and bike down to where the problem can be sorted out in a warm, dry and bright environment. A little chilled from the breakneck descent (breakneck in the sense that it was very fast and I also had a near miss with a large rabbit), I decide to stop for a hot drink …but the food is too tempting and they have these huge snuggly blankets! Before I know it, I’ve been there an hour. More riders are coming in now, wet and bitterly cold. The weather’s turned nasty out there and no one is enthusiastic about going back out just yet. In the sports hall, the mattresses are starting to fill up.

I haven’t slept since yesterday morning. I’m not ready to go horizontal at this stage – that can wait until the hotel – but, tucked into the corner of the eating area, I set my phone to vibrate in 45 minutes and pull the blanket over my head.

At some point, renowned randonneur Judith Swallow comes in and I hear her observe that it must be me under the blanket as I’m the only person mad enough to sleep in a chair when there are mattresses available.

She knows my foibles well. I wake briefly and reset the alarm for another 45 minutes. When I wake, the canteen is full of snoozing riders; the mattresses are all taken.

It’s stopped raining and I leave the comfort of the Alston control at about 1.30am. I know I’ve overstayed; I’d planned not to stop at all and I’ve been here for more than three hours. My aim of getting to Edinburgh by 11am is looking increasingly unachievable but that’s nothing to worry too much about. If I cover the next 185km in 12 hours, I’ll still have time to take a decent sleep at the hotel and be back on the road before the control closes. Sure, there are some lumpy bits ahead, but it’s downhill all the way back, isn’t it?

Feeling gravity’s pull

My recollection from 2009 of the road from Alston to Brampton, all 32km of it, is of an energy-sapping succession of short, sharp climbs and equally short, sharp descents. I’m not looking forward to it. However, perhaps the lengthy break has put some fire back into my legs and I quickly settle into a comfortable rhythm, even passing several other riders along the way, and I’m pleasantly surprised to find myself at Brampton just after 3am.

This control is being run by Heather Swift, a very experienced randonneur, and her understanding of riders’ needs is evident from little touches such as the numbered cards that are attached to my shoes when I take them off (to avoid metal cleats damaging wooden floors) and the drying lines in a sheltered courtyard for riders to hang up wet clothes while they eat or sleep. The food is good too, but I exercise more discipline than earlier and I’m back on the road, well-nourished, in an hour.

There are two recommended routes for the next section, to Moffat. One is a bit lumpy and has some poor road surfaces. The other is a couple of kilometres longer but not lumpy. Having grumped through the hilly sections between the Humber and Barnard Castle, I’m happy to do a few extra kilometres to avoid any unnecessary climbing.

Later, talking to people who chose the shorter option, I’ll hear many negative comments about that particular route, but I have to say that the “long” route ranks as possibly the most dreary 75km I have ridden on any Audax event. The noticeable deterioration in the quality of the road surface once I cross the border into Scotland doesn’t help my mood. It’s around this point that my attitude toward the ride starts to change from relishing the challenge to simply wanting it to be over. Now it’s not even Type 2 fun.

Moffat is pretty busy, with a fair number of both early starters and faster riders having slept there. Most have already moved on by the time I arrive, at 7.20, but there are enough passing through to ensure that I have plenty of company when I leave, just over an hour later, for the final 80km push to Edinburgh. I’ve got just over 12 hours until the control closes so I’m feeling very relaxed.

This is a stage of two distinct halves. It starts with an invigorating 10km climb of the Devil’s Beeftub. The surface is good; the gradient stays comfortably around 3.5-4.5%; and the view just gets better and better. Unless you’re obsessed with Strava segments, it’s a climb on which you can find a gear that works for you and simply enjoy the vistas as they open up before you. It certainly invigorates me and I start to shake off some of the grumpiness accumulated on the previous stage. Once over the top, at 456m, I’m on the dream descent. After the steep and winding roads of Yorkshire and Cumbria, where descending is fast but needs concentration, this is the cycling equivalent of a green run in a ski resort – some 18km of gentle downhill, with glorious views to be savoured. Looking back, I think these 30km may have been my favourite of the whole ride.

But then, when I hit the A701 heading towards Edinburgh, the ride turns horrible. The surface is so bad that I can’t find words to describe it. With every turn of the wheels my hands feel as though they are being pummelled with rocks. I try various ways to alleviate this – riding one handed and alternating hands; placing my hands flat across the tops of the bars; rolling my hands into balls and balancing them precariously over the brake hood – but nothing helps. There’s even no comfort to be found from moving more towards the centre of the road; it’s all bad and there’s too much traffic in both directions.

As I get within about 15km of the Edinburgh control, the traffic starts to get heavier and more aggressive; my mood is getting progressively darker. Just after a short but brutal and heavily trafficked climb near Auchendinny, the route turns off down a quiet lane that turns into a shared use path. I find myself wondering how some of the larger groups had coped with this as it’s far too narrow – and busy – for an undisciplined peloton. Later, I learn that one Italian rider, in fact, ended his ride on this section by crashing into a bollard.

The cycle path dumps me out on to a roundabout just off the city bypass and from there it’s a short climb to the control at Gracemount High School. A professional-looking photographer is snapping riders as we arrive and I try to strike a nonchalant (i.e. not bloody knackered) pose as I roll in. A cheerful volunteer greets me with “Welcome to Edinburgh” and I hurry inside to get my brevet card stamped. It’s 12.37, about an hour and a half later than planned but still more than eight hours before the control closes.

I stay long enough to have a cup of tea and collect my drop bag, with a change of clothes and a few other items. Then I’m back on the bike, heading another couple of kilometres into the city to the room I’ve booked at the nearest Travelodge. Of course, I’ve given no consideration to how I’m going to carry the drop bag so I end up with it hanging around my neck and bouncing against my ribcage like an under-inflated football.

A word on my mood at this point in time: I’m glad to have made it this far and I’m still feeling fairly fresh but I’m also aware that the last 40km or so have soured my attitude towards the ride. My hands are bruised and tender and I’m worried that riding on will make them worse. The roads weren’t as bad in 2009 but, even then, by the time I finished I was barely able to change my gears. I’m unsure whether to carry on or to call it quits and take a train back to London.

At the hotel, I shower for the first time in two days and call home for some reassurance and encouragement. In conversation, I come to the conclusion that there are three further points on the route back – Brampton, Pocklington and Spalding – that are close enough to a town with a mainline station to allow me to bail out, so I may as well at least start the return leg and see how I get on. I flop into bed and sleep for six, uninterrupted, hours.

Get up

Around 8pm I’m back on the road, refreshed, showered (again) and in clean kit. Then I make two mistakes. The first is to take a wrong turn leaving the city centre, adding several kilometres to the ride back to the school, where I plan to eat before setting off on the next leg. The second is to spend far too much time chatting at the control, yet again, with the result that I don’t leave until around 10.30, almost two hours after the last time that I should have.

I’m still relaxed, though. I’ve got more than 57 hours to get back to London and the sleep has done wonders. It’s a pleasant evening, 15 degrees, and I recall from 2009 that this stretch is hilly but not gratuitous.

About 5km out I pick up a small group of followers, most of whom appear to be from south-east Asia. Over the next 20km of steady but unchallenging climbing, all but two drop away; these two seem determined to stick to my wheel, to the extent that when I stop for a call of nature, they stop too! All my attempts to engage in conversation fail so I resign myself to their silent presence as we trundle down a short descent before starting the final climb of this leg. They seem nervous on the descents and on the fast final 12km drop into Innerleithen I lose them completely. Wheelsuckers aside, I’ve thoroughly enjoyed this stage; the stars are out and there’s barely a hint of wind.

The difference between this and when I rode it in 2009, in fiercesome winds and driving rain and sleet, is stunning. But it’s become cold. By the time I reach Innerleithen it’s down to 4 degrees and 25 minutes of fast descending has left me feeling more than a bit chilly.

Joy! More big snuggly blankets. The most amazing Scotch Broth (three helpings). And, among the volunteers, Denise, whom I know from the 2009 ride and numerous Essex rides, who comes over for a chat.

This has probably been my favourite control yet and, of course, I stay a bit longer than planned but I’m back on the road just after 2am. It’s still chilly, but I know that the next 10km are uphill and there are another couple of decent climbs in the subsequent 40km so I’m not concerned. It will be dawn in a couple of hours and the temperature will quickly rise.

It’s narrow road to Eskdalemuir, mainly used by logging trucks. I’m trundling along with another rider, whom I met on the 600km Brian Chapman Memorial a few months back, when we encounter one coming towards us. Even in the dawning light we can’t miss it. It’s lit up like something out of Close Encounters of the Third Kind and fills the entire road. We pull over to one side to let it pass but it stops. The driver has already encountered a number of cyclists and wants to know what we’re all doing on this normally quiet road. He’s gobsmacked when we explain and wishes us luck, warning us to take care because some of his fellow truckers can be less considerate of other people on “their” road. At the next control I hear that a group of riders had been forced off the road by another truck driver who simply drove towards them without even slowing .

A quick snack at Eskdalemuir is enlivened by meeting some of my fellow ACME (Audax Club Mid-Essex) riders. We don’t all set off together but from time to time over the next 60km back to Brampton I hook up with several of them. When we reach Longtown, after 40km, we rejoin the northbound route. Apart from a short stretch near Barnard Castle, from here until St Ives, back in Cambridgeshire, we are going to be retracing the route already taken. Every glorious descent will become a grumpy climb, and vice-versa.

I decide to mark this occasion by stopping at a cafe that is just opening for the day. One thing I’ve learned on long randonnees is that where food is concerned you should always listen to your stomach. If that means rice pudding at two in the morning, so be it. However, at this point – about 8am – there is nothing more appealing than the prospect of a hot bacon roll.

Somehow, though, I’ve managed to pick Cafe Grumpy. I breeze through the door with a big smile and ask if they are open for hot food yet.

“Hot food’s at the back,” barks a woman laying out loaves, without looking up.

I walk to the back of the cafe where there’s a small serving hatch in front of a kitchen area. The lady behind it is equally dour.

“Do you do hot bacon rolls?,” I ask, optimistically.

“There’s a menu on the wall,” shouts the woman at the front counter, in an exasperated tone. The woman behind this counter doesn’t speak.

The menu does, indeed, include hot bacon rolls and I order one, which is prepared in disinterested silence. I wander outside, where the temperature is lower but the atmosphere is decidedly less chilly, and a few other riders, including Jason, one of the ACME crew, stop for a second breakfast too.

Who knows? Maybe as the morning wears on the cafe staff will register that there is a lot of potential passing trade and cheer up a bit, but as a welcome back to England they are pretty uninspiring.

The bacon roll is good, though.

A third breakfast at Brampton goes down well and it’s good to see Caroline, another of the Essex contingent, who is working as a volunteer in the kitchen there. I’m feeling pretty positive now, knowing that once the next stage is out of the way all of the big climbs are over and, depending on the route taken, it’s a relatively benign ride back to London.

Bad day

The next six hours put an end to that optimism. Climbing out of Brampton is fine and I’m encouraged by not really noticing the short and sharp climbs as much as I had in 2009. Then, a few kilometres before I reach Alston, the weather starts to turn. The wind has been rising for a while and now comes the rain to join it. With that, the temperature drops.

I know that there is a large service station-cum-supermarket on the approach to Alston so I opt to get myself there, get a hot drink inside me, and then put on such wet weather clothing as I have, before tackling Yad Moss again. As it happens, I’m not alone in having this idea and I join a bedraggled group sheltering from the rain while sinking a milky coffee.

I know I’ve got to get going again at some point. After about 20 minutes the rain eases a little and a handful of us set off for the town centre. Most of us walk up the steep cobbled street. The cobbles are difficult enough to ride on when dry; rain makes them like a ice rink. I’ve been looking forward to this part of the ride. Southbound, it’s a shorter climb and, although steeper than the northbound route, it rarely rises above 6% so it’s easy to get into a steady rhythm and winch your way up to the top. Once over, it’s a long, long steady descent through Middleton and on pretty much all the way to Cotherstone, just 8km from the control at Barnard Castle.

In 2009, I hit 70kph on this stretch of road without much effort and, given that I’m a few kilos heavier than I was then, I’m anticipating an even faster run down.

However, the weather gods have decided that it’s not to be. I’m barely out of the town when the rain begins to pummel down. It’s that omnidirectional rain that seems to get you from every angle: piercing your face; dribbling down the back of your neck; and bouncing up off the road to frustrate your mudguards’ attempts to keep your backside dry. And with it comes the wind. When not pushing me back towards Scotland, it’s buffeting me sideways, forcing me to grip the bars tightly to stay in line. I’m now struggling keep my speed in double figures.

On the way up, I see another rider stopped by a parked van and, apparently, getting a drink. In my weatherbeaten frame of mind, I inwardly snark at the idea that someone is breaking the cardinal rule of Audax by having a support vehicle on the route. It’s only after the event that I learn that it’s veteran randonneur Drew Buck’s van and he’s cheerfully dispensing hot drinks to anyone who needs them. I wish I’d stopped

.

I pass the ski station. Almost at the top, I’m thinking, and I can ease off. Fat chance! If anything, the wind is even stronger on this side and, while I’m getting a little bit of assistance from the gradient, I’m still having to pedal hard to keep moving. The visibility is appalling and, to add to the fun, I’m starting to encounter some annoyingly thoughtless driving. The worst example is yet to come, but when I’m struggling to stay on the road the last thing I need is someone who can’t be bothered moving out to overtake.

I do manage to get up a bit of speed, peaking at a white-knuckle 34km/h, but it’s not quite the Bardet-like descent I was anticipating when I left Brampton. The sun-kissed drop off the Devil’s Beeftub yesterday morning seems like a distant dream. To cap it off, as the road narrows on the approach to Middleton, still in driving rain, an articulated lorry passes me at high speed so close that I am sure the driver is trying to shave my legs. It’s the scariest moment of the ride so far. I guess cycling the best part of 1,000km in the UK before having my life seriously threatened is pretty good going, though.

After Middleton, it’s a pleasant back road route to Barnard Castle, a small variation from the northbound route. Even better, it’s stopped raining although it’s going to be a while before I start to dry out. I hook up for the last stretch with a German rider. After yet another ridiculously close pass, he expresses his exasperation at the standards of driving here. I nod, silently hoping that he gets to cross Lincolnshire, which I often think of as offering the nadir of English driving standards, at night when the roads will at least be relatively quiet.

The control is at a large private school. The refectory is festooned with photographs of rugby players; someone who knows about these things tells me that a couple of them are famous. I’m more concerned about getting some of my kit dry. It’s a widely shared objective. Almost every possible place on which to hang an item of wet clothing is taken up but I still find a few places for the thing that I need to put back on. Experience has its benefits – I’m carrying spare socks and gloves in a waterproof bag and so long as my feet and hands are dry, I’m happy.

Again, I’m under a blanket, warming up. I chat for a while with Allen and Jonathan, both of whom I know from numerous Essex rides. We’d left Eskdalemuir at around the same time this morning, but they had pressed on while I stopped for a comfort break and had been through the Brampton control much more efficiently than me so have been here for a while already. I’m still eating when they leave. Then something odd happens. The room fills up with teenage boys, most of whom seem to be the size of outside toilets, if you get my drift. I assume these must be members of the school rugby team, although I can’t understand why they are here in the middle of the holidays. Whatever the reason, they form an orderly line for the food counters and, quite literally, fill their plates. I can’t quite believe how much they are eating. There seems to be bit of grumbling from arriving riders, who find themselves at the back of the queue, but the volunteers resolve the situation very quickly. Then, as suddenly as the arrive, the rugby players are gone. As I should be.

Outside, I bump into Alison, who is just about to leave. I’d seen her at both Eskdalemuir and Brampton and she seemed to be still going strong then. She’s hooked up with another, much older, rider who seems to have taken it upon himself to ensure that she make it back to Loughton. Certainly, from what I’ve seen so far today he’s paternalistically determined that she won’t waste too much time at the controls!

And he’s also keeping the pace up on the road. I follow them out of the school entrance and for the first few kilometres I keep them in my sights, but, with him leading and her locked to his back wheel, they soon pull away and I’m happy to let them go. I know the next section is a series of small climbs and descents so it will be harder to maintain a steady rhythm. It’s also one of the more scenic stretches, with some great views opening up towards the North Yorkshire National Park, so I’m happy to play tourist.

At the same time, I’m still feeling battered by the crossing of Yad Moss and I’m conscious that York – one of my potential bailing out options – is not that far from the next control, at Thirsk. Once there, I’ll take stock and, if I’m still feeling unenthusiastic about the ride, get some sleep and try to get an early train to London tomorrow.

The return route is identical the northbound one and so, about 7km from Thirsk I pass through the rather pretty village of Newby Wiske. I’d noticed this on the way up because it seemed that almost every house and lamppost was sporting a notice angrily demanding that “PGL GET LOST”. PGL is a company that hosts activity breaks for children – my own son has been on a couple with his school – and which, I learn from some of the posters, is turning a disused site on the edge of the village into an activity centre. It seems the residents of Newby Wiske (which I immediately rename Nimby Wiske, of course – you didn’t expect originality, did you?) don’t like the idea of children enjoying healthy outdoor activities such as rope swings, climbing, zip wires and field games, so are trying to block it. Given that for some of the kids that visit from schools in more deprived areas, a few days at PGL may be the closest they get to a proper holiday, I can’t muster up a great deal of empathy for the objectors. Then, as I reach the village sign and the first of the Get Lost posters, I encounter a lone woman, standing in her front garden, applauding me. Maybe I was too hasty to judge.

I stay only 40 minutes at Thirsk – enough time for a quick snack and to check out the options for taking a train from York. It doesn’t take much to convince me to carry on – the prospect of paying £122 for a walk-up fare does the trick. And I’m actually feeling refreshed. Taking that last stretch at a gentle pace has helped recharge the batteries a little, so I decide to press on to Pocklington, where I can at least have a hot shower and change into some clean and completely dry clothes.

However, rather than follow the recommended route, which I had found gratuitously hilly on the ride north, I opt to take advantage of the quiet night time roads to pick up the main road to York, go through the city centre, and continue on the main York to Hull trunk road almost all the way. During the day the whole route would be a nightmare of fast-moving traffic but, leaving the control at about 11pm means I enjoy almost empty roads all the way and it’s a pleasure to be riding on smooth tarmac for a change. Admittedly, I divert somewhat from the optimal course when I reach York itself, but at least I get to see the Minster, which I last visited on a school trip when I was 12. The only bugbear is the headwind, which is starting to increase. I’d picked up ominous comments from the volunteers at Thirsk about the wind becoming a problem overnight. This isn’t too much of a distraction, but I hope I’m not going to have it in my face when I cross the fens tomorrow.

I’d originally planned a hotel stop near Pocklington but had cancelled it on Tuesday when I realised that I would be arriving too late to enjoy it sufficiently. I breeze into the control at about 2.30, grab my drop bag and head straight for the showers, which are in another block. Unfortunately, the shower block is lacking two things; the promised towels and any hot water. So I sluice myself briefly under a trickle of cold water and deploy the usable parts of my discarded kit to dry myself.

There are mattresses available here but I don’t plan on staying longer than I need for a catnap in a chair and some breakfast. I put my head down and wake up an hour later to find myself surrounded by ACME riders, who have had some horizontal sleep and are now in a feeding frenzy. Disappointingly, “breakfast”, by which I mean something like cereals, is not going to be made available until 5am, so I gorge on toast, muffins, yoghurt and lots and lots of coffee. I leave, just after the ACME peloton, at a quarter to five, with 98km to the next control, at Louth. The sleep has helped and the first part of this stage should be pretty easy.

It is, and I’m in something of a zombie mode. Physically, I’m still going at a steady pace but mentally I’ve detached from the ride. I’ve got 350km or so to go and the quicker I can get it over with, the better. The wind is getting stronger; my hands are hurting; I’m bored with this route; and I’m done.

Everybody hurts

So I slog on to Louth. I’m not alone; there are plenty of people, including some very experienced Audax riders, pushing their way into the wind and some are already resigned to not finishing within the time limit. I’m starting to wonder if I should count myself among them. Possibly as a result, I spend too much time at the control. It’s been restocked with food so I take advantage of it. Outside, bikes are being blown over by the wind, which is now blowing steadily at around 30km/h. The next stage is not going to be easy.

As I’m leaving, a volunteer is reasoning with a rider who wants to quit. She points out that it’s about 30km to the nearest railway station, which is more than a third of a way to the next control, at Spalding, so he should consider carrying on as it will be easier to get a train there. Another volunteer is helping a rider who appears to be suffering from Sherman’s Neck to create some kind of a towelling brace so that he can keep his head up and continue, while at the same time advising him not to do so.

Not for the first time this week, I’m struck by how well-served this ride has been by the army of volunteers at every stage. I know from doing it in 2013 how much work is involved in volunteering and I take my cap off to every one of them.

The next 85km are horrible. Another rider, after the event, tells me how scenic he had found it, but I’m too busy battling into the wind to notice. More than half the stage is pancake flat but it feels like riding uphill. Somewhere near Boston I get to see the Red Arrows practising. At the time, I’m with a rider from India and I try to explain to him what they do. He looks at me blankly and is more concerned about a plan he is making (with no encouragement from me) for he and I to ride to the finish together so that he – in the group that started 15 minutes before me – will make the cut off. He wants to know exactly what time I will leave Spalding and precisely what time I will arrive at and leave St Ives. In this wind, I don’t even know what time I will arrive at Spalding. Eventually he takes the hint and latches on to someone else who is riding a bit faster than I.

On the approach to Spalding, I’m overtaken by a rider wearing “local” kit. He offers a few words of encouragement as he passes and invites to join the line. It’s not a bad offer; he has some eight or nine LEL riders strung out behind him and he is cheerfully towing them all to the control. I think that technically it’s a breach of the Audax rules on being assisted by non-participants, but I don’t think I’d recognise any of these riders again (and if I did I wouldn’t tell). And, annoyingly, they’re going just a bit too fast for my tired legs to let me tag along, so I trundle on, surprised at how much traffic there is for such a small town, and somehow manage to sail straight past the turning for the control. I double back and retrace, finally turning into the school gates at 6.15.

It’s taken me 5 hours to cover 85km; the next leg is only 60km but it’s over flat and exposed roads and straight into a wind that shows no sign of relenting.

At each control since Brampton, the volunteer marking my brevet card has cheerfully reminded me that I am technically “out of time” – in other words, I’m arriving at the control later than the time by which I should have left it. This gulf was at its worst at Innerleithen, due to my stupidly late departure from Edinburgh, and I’d reduced it to just a few minutes by the time I got to Louth, but I’ve now lost time again.

As I eat, I try to work out whether I am likely to finish the ride within the time limit. There are only 180km to go and, if leave the control by 8pm, I have 12 hours left to cover them, so there shouldn’t be a problem. But there’s the wind; the residual tiredness from having already covered 1260km with comparatively little sleep; the reality that riding at night is always a little slower than in daylight; and the knowledge that the final 70km or so feature a succession of short but energy-sapping hills, all to be factored in.

It’s do-able. And I’m encouraged by the sight of the rider who had been contemplating abandoning at Louth coming through the door, looking windswept but satisfied.

I leave Spalding just after 7.30pm. The first 15km are alongside the River Welland. There’s no shelter from the wind so it’s simply a case of grinding along. I can see riders both ahead of and behind me, all making equally slow progress. No one gets any closer, nor more distant. It’s as though we are all connected by an invisible thread. Turning away from the river at Crowland, the road continues across the fens, through Whittlesey and Thorney still dead flat but feeling like a long drag uphill. The roads are mostly empty but somewhere near Ramsay a passing van slows down right next me and the passenger leans out to scream drunkenly. Maybe he’s incoherent or maybe I’m past caring, but I can’t process a word he’s saying so I merely shake my head like a nodding dog on the back shelf of car and say nothing. The van speeds off and the silence descends once more, broken only by the steady whirring of my chain winching the rear wheel onwards.

The road’s rising and falling a little now – not enough to warrant a gear change but sufficient to give me odd moments of being able to coast, a welcome relief after a couple of hours of having to ride a geared bike as though it were a fixed wheel, never stopping pedalling. However, on the negative side, I realise that I am starting to hallucinate. Roadside trees are turning into large white rabbit-like creatures while the road itself appears to be underwater. I recognise this from the penultimate stage of LEL in 2009 when I was convinced that I was being followed by giant chess pieces. I’ll have to stop for some sleep at the next control; it’s too risky to carry on without it.

Fortunately, St Ives comes into view fairly soon. On the run-in to the control I spot a small group of riders from Thailand that I’d seen at previous controls but this time they are riding in the wrong direction. I shout and wave my arms around but they take no notice. I hope they realise their mistake soon.

Then I’m distracted by a couple of souped-up sports cars with vanity number plates who are clearly using the outskirts of the town to race. Just ahead is a junction with two lanes at the traffic lights, which are on red. The first car screeches to a stop in the right hand lane but the second drives straight through at high speed. With a roar of acceleration and over-revved gears, the first car also runs the light and screams away. I’m relieved not to have encountered these two clowns further back. Then, to add an extra moment of weirdness, the same van that I had encountered earlier comes past again, the passenger still shouting out of the window. It’s a strange place, north Cambridgeshire.

Can’t get there from here

My brevet card is stamped. It’s 11.25. Eight and half hours left to cover just 120km, but I am very hungry and I desperately need to sleep – and for more than a 45 minute catnap. This is the point at which I realise that I’m not going to make it back in time. Although it’s late, I call home to tell my wife, who will be coming to drive me home from the finish, not to hurry in the morning because I won’t be there for 8am.

“I’ll send you a message when I’m leaving Great Easton,” I tell her.

Dejected, I take a cup of tea and some cake from a smiling volunteer and slump in a chair in one corner of the hall. There are plenty of riders sleeping here, but I know from the frame numbers I’ve seen on the other bikes parked outside that most are in groups that started much later than me and have four or five hours more still in hand. They can sleep for several hours here and still cruise to the finish. My plan now is simply to ride back, getting there whenever I get there, because there really isn’t a better option. I could ride to Cambridge and take a train back to London, but I figure that even finishing the ride out of time is better than bailing out so close to the end.

I lean onto the table, put my head down on my folded arms and drift almost instantly into unconsciousness. Suddenly, it’s 1am. Looking around, I can see that the control is starting to wind down, in anticipation of the last riders leaving. Although I’ve probably slept for little more than an hour, I feel wide awake and full of energy. I fetch another cup of tea and some more food. I wolf down the food and, after layering up against the expected cold, I’m back in the saddle at 1.20.

The first part of this stage is rather unusual as it follows the Cambridge Busway, a dedicated bus route that has a cycle track running all the way alongside, for about 18km before turning off to go straight through Cambridge city centre and then on to Great Easton. I hook up with another rider, Fred (I didn’t get his surname), who had started about half an hour later than me but is also having some doubts about finishing in time.

As we ride down the deserted busway – a slightly surreal experience, especially when we encounter a couple of somewhat inebriated youths riding unlit bikes in the opposite direction – I explain to Fred that the “official” route between Cambridge and Great Easton involves meandering lanes and a lot of “up and down”. That route’s been chosen because the main road from Cambridge to Saffron Walden is a terrifying racetrack during the day, with aggressive driving and close passes guaranteed. However, at 3 in the morning, I anticipate it being a lot quieter so I suggest we try it.

The difference in distance is minimal – about 5km – which doesn’t concern me as the ride overall is more than 40km over distance, but, as with the main roads in South Yorkshire, it will be a much more pleasant ride on better surfaces. I know from riding them many times that the lanes in north Essex are often in very poor condition.

It proves to be a good move. Apart from a near miss with an inattentive minicab driver in the city centre, we hardly see another vehicle between there and the control. I feel as though we are belting along – certainly, my legs are spinning happily and I’m no longer conjuring up giant furry roadside creatures – although, looking back at the Garmin data afterwards, I see that our average speed is only around 16km/h for the 66km. I know this part of the route in my sleep and Fred is happy to lock in behind me, although he does ask, as we cover the mini-rollercoaster between Saffron Walden and Thaxted, how many more “bloody hills” there are to go!

Shiny happy people

I’m looking forward to spending some time at Great Easton. I worked as a volunteer there in 2013, managing the kitchen, and two of my fellow volunteers, Grant Huggins and Gill Cooper, are running the show this time around. Knowing that I am out of time, I’m anticipating a leisurely breakfast and a chat with them before cruising gently back to Loughton.

But it isn’t to be.

We pull in at 5.19am. Fred’s feeling wasted and tells me that he’s going to rest up here for a while. I, on the other hand, am looking in amazement at the clock, realising that in my befuddled state last night I’d overestimated the time that it would take me to get here. As he stamps my brevet card, the volunteer at the front desk comments that I’m just within the cut-off time for the control.

“If you don’t hang around, you should make it back to Loughton in time,” he declares.

I don’t need much encouragement. I rush into the main hall to find Gill and Grant. Considering that they have probably had even less sleep than me over the past few days, they’re both looking surprisingly perky. One gives me a hug while the other tries to persuade me to stop for a cup of tea, but I decline. I’m sorry not to be able to spend time with them, but I also know that they’re going to be kept busy over the next few hours as the final bulge of riders comes through, so I’d probably be a bit of an unwelcome distraction. A quick look at the map in the entrance hall to remind myself of the route back and at 5.26am, I’m away.

Seven minutes at a control has to be my record – although I soon wish that I’d thought to refill my water bottles!

Again, the official route uses quiet lanes rather than the faster main roads but I know this area well and opt for another diversion. So, from the control I head uphill into Great Dunmow and then pick up the B-road through Fyfield to Chipping Ongar. Although it’s not yet 6am, the road’s already starting to get busy and, as it’s still quite narrow and winding in places, I enjoy far too many close passes for comfort. I’m not sure why it is that some drivers find themselves incapable of crossing the centre line even when the opposite lane is empty, but they do.

In Ongar, I stop at a shop, rush in and buy a bottle of water – more time wasted, I’m telling myself, but I’d run out of water some way back and am parched – and then turn back on to the lanes to pass the lovely old log church at Greenstead. At Toot Hill, I rejoin the official route, very happy that I’ve managed to miss the dreary climb up from Bobbingworth. It’s not steep but it’s just one of those stretches of road that I’ve always hated. Overall, I’ve shaved a mere 4km off the distance, but the real benefit has been being able to ride on relatively solid tarmac.

At Toot Hill I encounter a large group of riders – possibly Spanish or Italian – in matching kit who have stopped for a group photo and I’m afraid I can’t resist the temptation to photobomb them. So somewhere there may be a picture of a happy bunch of riders in club colours with a waving fool in an Audax England jersey passing through.

I don’t need help with navigation so I’ve got my Garmin showing me the time instead and I’m watching each minute tick away, knowing that even something as simple as a puncture could mean the difference between finishing and failing. But I’m starting to feel excited and the adrenalin is streaming into my legs.

At exactly 7.30, I cross the M25, having just been overtaken by the photographic posse, which is setting a cracking pace. I notice that none of them is carrying anything larger than a seat pack – a sure sign that they have a support vehicle in tow. Just over 7km to go. About 500 metres later, I turn off for the short climb towards Theydon Mount – and hit a traffic jam.

It’s a narrow lane, with head height hedges either side, and it zig zags up the hill with three blind 90 degree bends, before opening out a little to cross the M11. I immediately assume that the five or six vehicles in front of me are simply stuck behind the group that passed me a little way back but it turns out that the problem is a large horsebox van coming down the hill. The posse is having to squeeze past it single file and the driver has to find a place to pull in and allow the vehicles coming up the hill through. It seems like an age before we are all moving again, although in reality it’s probably no more than a couple of minutes. But as an infamous cyclist once wrote, every second counts.

I pass through Theydon Bois village, turning for Debden (as an aside, although LEL is described as starting in Loughton, the school used as the HQ is really in adjoining Debden Green). Again, I know this road well but for some reason this morning it seems longer than usual so it’s a massive relief when I turn off and into the residential streets that lead to the finish. Even though I have barely 1km to go, I don’t let up. Up ahead, the posse has slowed down again and I stream past them on the approach to the school gates.

Once in the grounds, a volunteer tries to steer me towards the bike parking area but I’m having none of it. I have an irrational fear that something will still go wrong; that there will be a massive queue of riders waiting to check in or perhaps the computers will crash just before I get there.

“I’ve got about three minutes to check in,” I plead, exaggerating slightly, I know.

“Give me your bike,” he shouts. “Go for it!”

I abandon the bike and run – to the extent that I can run in cycling shoes – to the school entrance. The control desk is inside the door. There’s no queue; it all seems very calm. One person takes my brevet card while another passes me a medal.

“Well done,” she says with a smile.

It’s 7.54. I’m 11 minutes within the time limit.

Over breakfast – a fry up and a can of beer! – in the school hall, I catch up with various friends whom I had encountered at different points along the way and we share our war stories. There’s no sign of Tony or Alison, from the run up to Louth. Later I learn that Tony had to abandon on his second day, at Barnard Castle, again due to a persistent injury, and Alison, who had looked to be going so well, threw in the towel at Louth on the return leg. I hope to see them again in 2021, when I expect to be back in the red volunteers’ t-shirt.

Aftermath

As for me, I still felt relatively fresh at the finish and, as always with rides of this length, it was a couple of days before the sleep deprivation hit me. My biggest problem was with my hands, particularly the left, which, even now, almost four weeks later, is still tender and lacking its usual flexibility. I can’t even play my guitar, which is very upsetting, although probably being appreciated by the family.

I’ve experienced this before and I know that it’s usually a couple of months before everything gets back to normal, but this feels worse than I recall from past rides. We shall see.

There’s also, apparently, some doubt about whether my ride will be officially validated by ACP, which governs these ultra distance events. According to its rules -which I have heard are enforced strictly on Paris-Brest-Paris – arriving late at two consecutive controls means disqualification, even if you go on to finish the overall event in time. To be honest, I’m not too fussed about that, but it would be a bit of a shame, given that such a large proportion of riders (more than 40%) either abandoned or did finish out of time. So far as I’m concerned, I finished in time – and I have a rather large shiny medal to prove it!

Mentally, I’m feeling very unsettled. If I’m honest with myself, I didn’t actually enjoy most of LEL. For much of it, I was simply zoned out, thinking only of getting to the next control, and barely took in what I know to have been the superb and varied terrain through which I rode.

I could blame it on the road conditions, or the weather, or any number of factors, but I’m sorry to say that I’ve felt the same way on many of the Audax rides that I’ve done in the past few months. I’ve not ridden a bike since finishing LEL. That’s partially because of the pain in my hands but mainly because I simply don’t feel any enthusiasm for doing so.

Somehow, I have to rediscover whatever it was that made me fall in love with cycling in the first place. Perhaps that’s a topic for another piece, though.

*There were 1,500 entrants. I gather that, in the end, about 1,450 actually started.

August 2017

Postscript: The ride was validated. It was several months before I was able to use my hands properly again and, although I have ridden a few 600km events since, I doubt that I will ride LEL again. In 2022, I spent a week at the Brampton control as a volunteer. I probably got less sleep than I would have had I been riding, but at least I could still type afterwards!